Good Luck Postcards

“… We come to regard being alive and well as merely luck.”

—A private in the British Army, from a letter written on Christmas Day 1916.

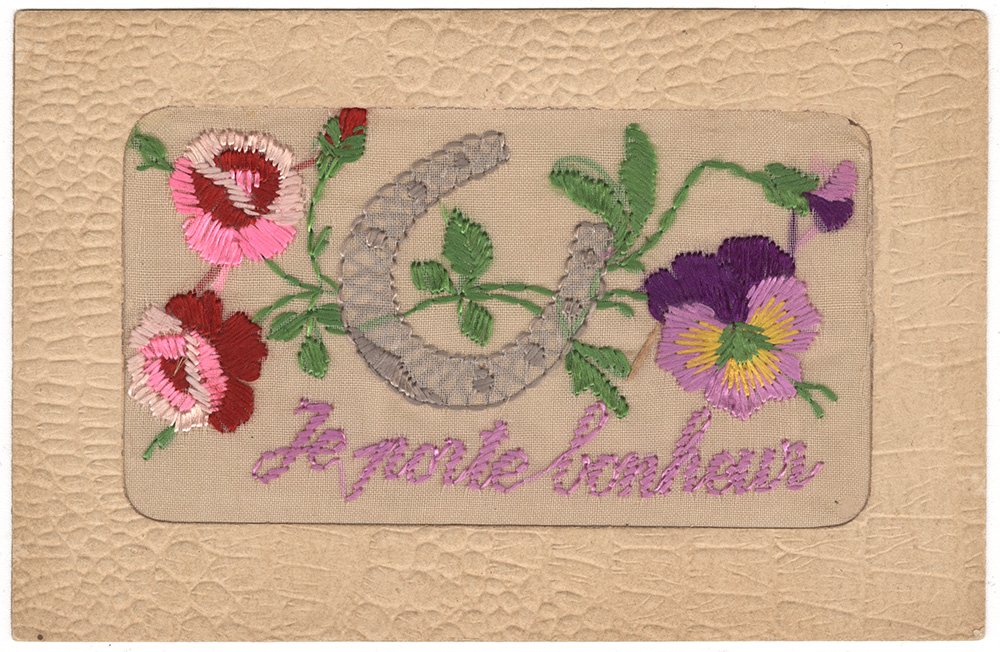

Easy to mass-produce and popular, porte bonheur (good luck) postcards sold in millions across combatant countries. Styles varied, but many postcards had silk embroidery and featured a symbol of good luck like a horseshoe, flags of the Allied countries or floral scenes. Though also manufactured in England and Switzerland, most porte bonheur postcards came from France. Nearly every shop in the French ports of Calais, Boulogne and Dieppe sold them to soldiers passing through.

Porte bonheur postcard

France

c. 1914-1918

Object ID: 2023.53.1

National WWI Museum and Memorial

“I bring good luck,” reads this silk postcard embroidered with pansies, violets and a horseshoe. The horseshoe is perhaps the most recognizable marker of good luck. In British and French tradition, the horseshoe provided protection against witches, leading to the charm's commercial success as a token of good luck in the war.

Good luck postcard

France

1915

Object ID: 2020.138.1

National WWI Museum and Memorial

Silk postcards often combined patriotic images with expressions of luck. In this example, the postcard depicts flags of the Allied nations (Russia, Italy, Great Britain and France) as individual petals on a four-leaf clover, or lucky shamrock. The year 1915 and hopes for “Good Luck” follow. The flags of the four allied countries united in a single lucky symbol reminded soldiers of their joint purpose in the war, and maybe brought them a bit of fortune in the trenches.

During World War I, armies dug long, narrow ditches in the ground in which soldiers could hide during battle or while waiting for battle. They could be scary and unsafe places.